NASA Glenn’s Arrival in Cleveland

In 1940, the NACA sought a location for its new engine research laboratory (today NASA Glenn Research Center). Cleveland, Ohio’s aviation industry and renowned airport made it a leading contender for the site, but it was the steadfast effort of a small cadre of local officials that secured the agreement. The endeavor has generated over 75 years of technical and economic impact for Cleveland.

Overview

The NASA Glenn Research Center is an essential component of the Cleveland community, but if not for the work of determined local officials in 1940, the laboratory could have easily ended up in Chicago or Dayton. Today, Glenn’s nearly 3,300 employees resolve a variety of technological and scientific issues for both industry and the Government. The center, however, began in 1941 as an engine research laboratory for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA).

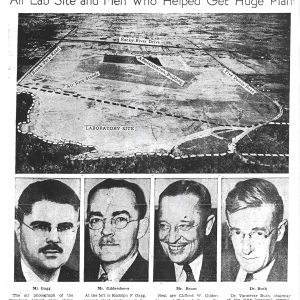

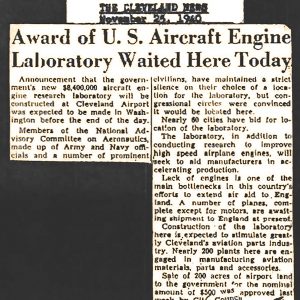

As the United States participation in World War II became imminent, the NACA sought to construct two new research laboratories. Localities across the nation, including Cleveland, Ohio, vied to have the facilities situated in their region. The NACA devised an objective method to evaluate the bids. Cleveland and a Chicago location ranked the highest of the 72 submissions. When NACA officials reconfigured their ranking criteria, Cleveland gained a slight lead. The local power company then agreed to discount its electricity rates, and the deal was secured. The NACA announced the decision on November 25, 1940. A groundbreaking ceremony took place on January 23, 1941.

Documents

- Site Selection for the NACA Engine Research Lab by John Holmfeld (1967)

- “From Inertia to Action” from Engines and Innovation (1991)

- “Rising from the Mud” from Bringing the Future Within Reach (2016)

Cleveland–An Aviation Center

As European nations demonstrated the importance of aircraft during World War I, manufacturers in Cleveland, Ohio, moved into the emerging field of aviation. The Steel Products Company (later, Thompson Products) became the first by applying its automotive valve technology to aircraft engines. In 1917, Glenn Martin agreed to relocate his aircraft factory, the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Company, from California to Cleveland where he designed the nation’s first twin-engine aircraft and bomber. Martin employees went on to establish the Douglas Aircraft Company, Bell Aircraft Corporation, and North American Aviation.

Martin, who was active in Cleveland civic activities, was a key figure in the establishment of a local airmail link to Chicago in 1919. In 1921, city officials agreed to build a municipal airport on 1,200 acres southwest of the city. John Berry was responsible for the design and management of the facility. The Cleveland Municipal Airport was the largest in the nation when it began operation in 1925. It produced innovations such as the first control tower, first ground-to-air communications, first passenger terminal, and first runway lights. By the late 1920s, Martin’s aircraft had outgrown the Cleveland facility, and he moved his operations to Baltimore.

In 1929, two local aviation manufacturers, Frederick Crawford of Thompson Products and Louis Greve of Cleveland Pneumatic Tool, arranged for the city to host the National Air Races at the airport. The 3-day annual included several types of races and various aeronautical demonstrations. Thousands of Clevelanders filled the large grandstand along the western edge of the airport and many more watched from local streets and rooftops as the racers passed overhead.

By the 1930s and 1940s, Cleveland was the nation’s sixth largest city. The Great Depression, however, brought massive unemployment and political volatility. The 1935 election of Harold Burton as mayor brought stability and the introduction of the Works Project Administration that created thousands of local jobs and produced new highways and bridges and upgrades to parks, markets, and other cultural attractions. By 1939, Cleveland manufacturing was returning to its pre-Depression levels. The city was again on the cusp of prominence at the time the NACA was searching for a home for its new research laboratory.

Documents

- Aerospace Industry from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

- Glenn L. Martin Company history (2003)

- Cleveland Airport Advances (1944)

- Cleveland Hopkins Airport Historical Info (1990)

- Cleveland Air Races from Air Racing History

The NACA Expands for War

The NACA, established in 1915, was originally a committee of aviation experts that met periodically to help coordinate the nation’s aeronautical activities. In 1917, the group established a laboratory at Langley Field in Virginia to perform its own research. NACA engineers used the lab’s wind tunnels and other equipment to develop groundbreaking advances, such as its family of airfoils and the NACA cowl.

Both the NACA Director of Research George Lewis and committee member Charles Lindbergh spent time in the mid-1930s touring European aeronautical facilities, particularly in Germany. Although they did not consider the physical facilities to be superior to Langley, they were struck by the number of laboratories and researchers, many with specialized training unavailable in the United States. Unlike their NACA counterparts, German researchers were also focusing on propulsion, which resulted in aircraft that were achieving greater speeds and altitude than those in the United States.

In 1938, the NACA formed a committee to devise plans for a second laboratory and began looking for a site. Cognizant of the political pressure that municipalities would apply, the NACA created a neutral, systematic process for selecting the site. In June 1939, Cleveland officials submitted an unsuccessful bid. The NACA opted to build its new Ames Aeronautical Laboratory in Sunnyvale, California, with its Naval air station and year-round flight conditions. During the process, however, the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce’s Clifford Gildersleeve and NACA Executive Secretary John Victory formed a cordial relationship during the process.

In October 1939, Lindbergh led a committee that began identifying facilities and infrastructure requirements for an engine research laboratory. They unveiled plans for a proposed $10 million facility on January 23, 1940. Gildersleeve immediately began inquiring about the project, but it would be months before the NACA began its site search.

Documents

- Cleveland Hopkins Airport Historical Info (1990)

- Cleveland Airport Advances (1944)

- Congressional Memo Re Appropriation for AERL (1940)

- Cleveland Invitation to the NACA (1939)

The Scientific Ranking Process

In the spring of 1940, the NACA prepared to conduct its search for a location for the new engine research laboratory. Based on input from engine manufacturers such as Pratt & Whitney, the NACA revised the systematic ranking process used for Ames. The site evaluations would be based on 18 individually weighted criteria related to the physical setting, availability of utilities, and proximity to associated institutions. The primary requisites were a location next to a substantial airport, ample supplies of electricity and water, separation from the local community, and proximity to engine manufacturers. With war looming, emphasis was placed on sites in the center of the country, out of range of enemy bombers.

Congress formally approved funding for the engine lab on June 22, 1940, and the NACA immediately dispatched letters to potentially interested officials and municipalities. The notice included the list of desired site and community characteristics. The responses, some hand-delivered, began flooding in almost immediately. The proposals arrived from sites all across the nation, but the majority, including five in Ohio, were centrally located.

Cleveland officials quickly resubmitted the bid put forward in 1939. Local officials, however, quickly revised the submission to address the specific criteria for the engine lab. By mid-July, the NACA’s new Special Committee on Site began reviewing the 62 proposals. The team, led by Vannevar Bush, immediately dismissed 16 bids that did not meet the prerequisites.

On August 6, 1940, Bush drafted a team to visit the 20 most promising sites to verify the information on the submissions. It consisted of John Victory and Russell Robinson of the NACA, Army Captain Donald Keirn, and Navy Lieutenant Commander John M. Rutherford. Robinson, who was the only one devoted full time, performed most of the actual ratings and evaluation.

The team commenced their inspections in mid-August. Local officials and business leaders led them on a tour of the proposed location; discussed issues such as power, water, and drainage; and touted the community’s amenities and professional ties. The group spent August 22 and 23, 1940, in Cleveland. Clifford Gildersleeve; Frederick Crawford, President of the Chamber of Commerce; John Berry, Airport Manager; and A.C. Shepherd, Cleveland Electric Company, accompanied them. Crawford held a dinner that evening at the Union Club where local industrial leaders vowed to support the new lab.

When Bush’s Site Committee reconvened on September 10, 1940, Cleveland held a narrow lead over Dayton in the rankings. The search, however, was not over yet. In response to pressure from other locations, however, Victory and Robinson proceeded to visit 14 additional sites.

Documents

- Qualifications for New Engine Lab Site (1940)

- Requirements for Engine Lab Site (1940)

- Criteria Weights for Ranking Sites (1940)

- John Victory bio sketch (1958)

- Ratings of Ten Top Ranking Sites (1940)

Negotiations Commence

One thing delaying the final decision was the NACA’s concern regarding the disparities in electricity rates at the different locations. The new laboratory, particularly its large wind tunnel, required significant quantities of power to operate. It was at this point that John Victory decided to sidestep the objective ranking system and try to influence the process by negotiating lower power rates at several cities, including Cleveland.

Previously, the NACA fastidiously avoided the continual lobbying by various public officials, including Clifford Gildersleeve. NACA officials were courteously receptive but refused to make promises or divulge information. Now they were soliciting influence. During the first week of October 1940, the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company (CEI) agreed to Victory and Russell Robinson’s request to look into the matter, but made no promises.

In the meantime, several other localities adjusted their bids. When the Bush’s Site Committee reexamined the rankings on October 8, Glenview (just north of Chicago) had a narrow lead over Cleveland. There was deep concern, however, that Glenview’s adjacent airport was not publicly accessible. The members, who had other pressing responsibilities, were anxious to bring the search to a conclusion. To accelerate the process, Rudolph Gagg was brought in from Wright Aeronautical. The NACA had tasked Gagg with designing the facilities that were needed at the new lab.

Gagg accompanied Victory and Robinson to Cleveland on October 14. Sensing that time was of the essence, Gildersleeve prepped the key stakeholders for the visit. Air Race Association officials acknowledged that the event was suspended indefinitely, and the grandstands could be removed. John Berry extended the proposed lot all the way to the Metroparks ravine, giving the NACA a 1-mile boundary without buildings. And most importantly, CEI agreed to lower its rates making the cost of electricity competitive with other sites.

Documents

Cleveland Surges Ahead

The next day, October 15, 1940, John Victory recommended the selection of Cleveland, despite its second-place ranking. To justify the decision, the committee readjusted the weights of several of the selection criteria to give Cleveland a slight edge over Glenview. The committee met later that day to discuss the findings and conduct one last review of the top 10 sites. Each member then listed their top three choices. Not surprisingly, Cleveland emerged on top. A resolution was passed selecting Cleveland for the engine laboratory pending further commitments from the city to follow through on its promises.

Victory and Russell Robinson returned to Cleveland October 17 through 19 to ensure the city would uphold its commitments and to begin negotiating regarding the transfer of the title. City Law Director Henry Brainard drafted a resolution authorizing Mayor Harold Burton to offer the 199.696 acres to the NACA for $1 an acre. It ensured that neither the NACA nor the airport would build structures that interfered with the activities of one another, and that the land would return to the city if the NACA vacated the property. The NACA received permission to use the airport without charge, and it could remove any existing structures on the property. Cleveland City Council passed the resolution on October 21, 1940.

The discovery of several oil and gas line easements on the property delayed the final agreement, however. Meanwhile, the city increased the purchase price to $500 to cover unexpected title expenses. The NACA continued to keep the negotiations a secret until the final agreement was in place. Rudolph Gagg even took the step of removing all identifying marks from the site layout provided to the Langley team that was designing the facilities.

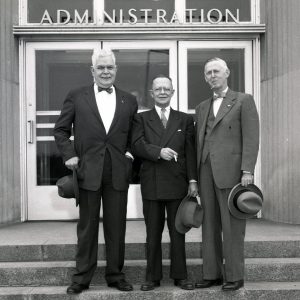

Brainard, John Berry, and Clifford Gildersleeve traveled to Washington, DC, on November 7, 1940, to resolve the legal issues. Brainard crafted the updated council resolution on the flight home. The Land Title Guarantee and Trust Company issued a preliminary title report on November 14. A week later, Brainard sent the resolution to Victory for review. Cleveland City Council approved the revised resolution on November 18, 1940.

Documents

The NACA Announces the Decision

“There seems to be something in the spirit of the people in Cleveland that makes effective cooperation seem easy,” John Victory told the press on November 25, 1940, while making the formal announcement that the NACA’s new facility would be located in Cleveland. “We look forward with pleasure to the development of our engine research laboratory in such a city.”

Cleveland City Council passed the final ordinance later that day. Mayor Harold Burton quickly signed it. The Board of Control adopted the ordinance the next morning, formally conveyed the city property to the U.S. Government.

Most of the competing localities were gracious and trusted that the Government had acted forthrightly. Dayton, however, which had also lowered its electrical rates, lamented the “wasting of our time” on the effort.

In the meantime, city officials began working with utility companies to support the lab, and the NACA brought in Federal surveyors to review the property. On December 3, 1940, the City of Cleveland received a $500 check from the Assistant U.S. Attorney General. The process was complete. Through a combination of inherent traits and the zealous work of city officials, Cleveland had risen above 72 competing sites in 61 other cities.

Documents

Groundbreaking

On January 23, 1941, local authorities, military representatives, and NACA officials converged in downtown Cleveland to celebrate the selection of the city for the new engine lab in Cleveland. It was 1 year to the day after the NACA formally proposed the new engine laboratory. In the morning, the group toured local manufacturing plants and viewed the production of landing gear for the massive XB–19 experimental bomber. They then proceeded to the Hotel Cleveland at noon for a luncheon sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce. Cleveland’s newly elected mayor Edward Blythin opened the event. Frederick Crawford then reminded area manufacturers of their promise to support the lab. A local hardware company George Worthington presented John Victory with a chrome-plated pick and shovel to be used for the groundbreaking. Victory described the NACA’s selection process and avowed, “Pressure and politics played no part in the decision.”

George Lewis stressed the importance of the engine lab, “Engine research is the chief factor in the development of military aviation today.” Perhaps the most rousing speech was by the Civil Aviation Authority’s Edward Warner. He said, “What we are doing here today may mean the difference between America’s survival and subjugation. The difference between winning a war and losing it may be the difference between [a] 1,000- and 2,000-horsepower motor, or the difference between [the] ability to fly at 20,000 feet or 30,000 feet.”

After lunch, the cadre traveled to the airport site for the ceremonial groundbreaking. William Hopkins, John Berry, Ray Sharp, Crawford, General George Brett, Warner, Sydney Kraus, Blythin, George Lewis, and Victory assembled on the cold field. Lewis struck the ground with the pick to loosen the soil. General Brett of the Army Air Corps then grabbed a shovel full of earth as a newspaper photographer snapped a shot. As General Brett lifted his shovel, Crawford joked that “Many an army rookie would like to see this.”

Actual construction began within days, and the new laboratory began operations in May 1942.

Documents

- AERL Groundbreaking articles (1941)

- Lewis Talk at AERL Groundbreaking (1941)

- Groundbreaking Shovel Found (2008)